At TableFables, one of our core informal “tenets” comes from a quote by the French gastronome Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin:

“Tell me what you eat and I will tell you what who are”

I like this quote because, well, it’s true both physiologically and culturally.

The person into fitness is a really good example of this. Calories are counted and macros are obsessed over. Bland food is then boiled and packed into cute little plastic containers.

So we know what and how much this fitness-person is eating. But, as we know, this and all eating is also sustained by a vision of eating. This fitness person has bought into a vision of what eating will do for them, what is “good” for them, who they are now, and who they want to be.

We see what they are made of—lots and lots of boiled chicken and broccoli—but even if we can’t articulate it, we instinctively know that it’s so much more than that. It’s about an almost Lent-like, ascetic fasting for the “gains”, which is for a type of body aesthetic, which is for a type of sexual appeal, which is for…and on and on. You get the point. Food is always a promise to take us “home”.

I want to think about this idea from a different angle. Last week, my fiancée, Eunice, who is currently studying Art History, shared this passage about French dessert culture in the late 20th century.

“Even in the 1990s, customers in French bakeries could choose to buy têtes de negres, “heads of negroes”, hollow chocolate-covered meringues: heads, that is, without nothing inside…I was dismayed not only by their existence, but by the nonchalant indifference and sheer arrogance of the name itself.”

Here’s what one might typically look like:

There’s much to say here.

The cultural indifference to this act of eating should surprise no one, especially in light of the US election and the Israel/Palestine conflict. That is how history works, unfortunately. People normalize moral horrors, and it takes a truly courageous person to shake people awake to reality.

To some extent, I can understand what this type of food would do to someone. Labeled as a Twinkie (for being yellow on the outside and White on the inside), I learned rather quickly that the value of Korean-American identity was dependent on my performance of certain cultural skills that would allow others to perceive me as “Korean enough” and “American enough”.

The fact that Twinkies are cheap and made in a factory adds to the insult. I am easily accessible, nutritionally worthless, gluttonously-satisfying, mass-produced. This is what it means to be a Twinkie.

And then there’s the Cannibalistic part. I am literally called an object that is then eaten. My identity is reduced to an object that satisfies your hunger. My humanity—if you can call it that—is consumed.

At this point, some readers might consider all of this to be a stretch. Like, is anyone really thinking about Twinkies like this?

To these readers, I get what you are saying. My point isn’t to say that there’s a single narrative on foods that act as racial slurs.

Rather, my point is that food has a tremendous power that opens doors to worlds of belief and identity. Food gets us to believe things about ourselves we would have never imagined otherwise. The narrative I shared above is simply one of many pathways in how food might form our identity.

Maybe the fact that this all sounds so unbelievable (to some of you) is also the point. Maybe food, when racist, creates paranoia. I’m tempted to believe things about myself that are simply untrue. Rather than cultivating wholeness, the realms of possibility are about instigating my insecurity.

For a long time, I used to lament that racism felt so easy, that all you needed to do was reduce someone to stereotypes and caricatures.

Real racial reconciliation, on the other hand, felt too hard because it required a depth of understanding built on humility, creativity, and deep empathy. Is there such a thing today, or ever?

If only we could heal racism as efficiently as it seems to infect us, then maybe we would stand a chance.

These days, though, I feel differently about efficiency. I find comfort and joy in the fact that what is beautiful and true is not about efficiency but the slow yet steady work that moves forward. As John Perkins eloquently writes, “True change works more like an old oak tree in the spring, when the new life inside pushes off the old dead leaves that still hang on.”

True change requires time, collaboration, cultivation, and when the season is right, new life emerges. Most of us don’t get to see the Promised Land, and maybe that’s okay, because it’s bigger than us. It’s not about getting to experience what we’ve always dreamed of, here and now. Rather, our hopes rest on the idea that one day, a future generation will experience real change because of what we’ve contributed in our lifetime.

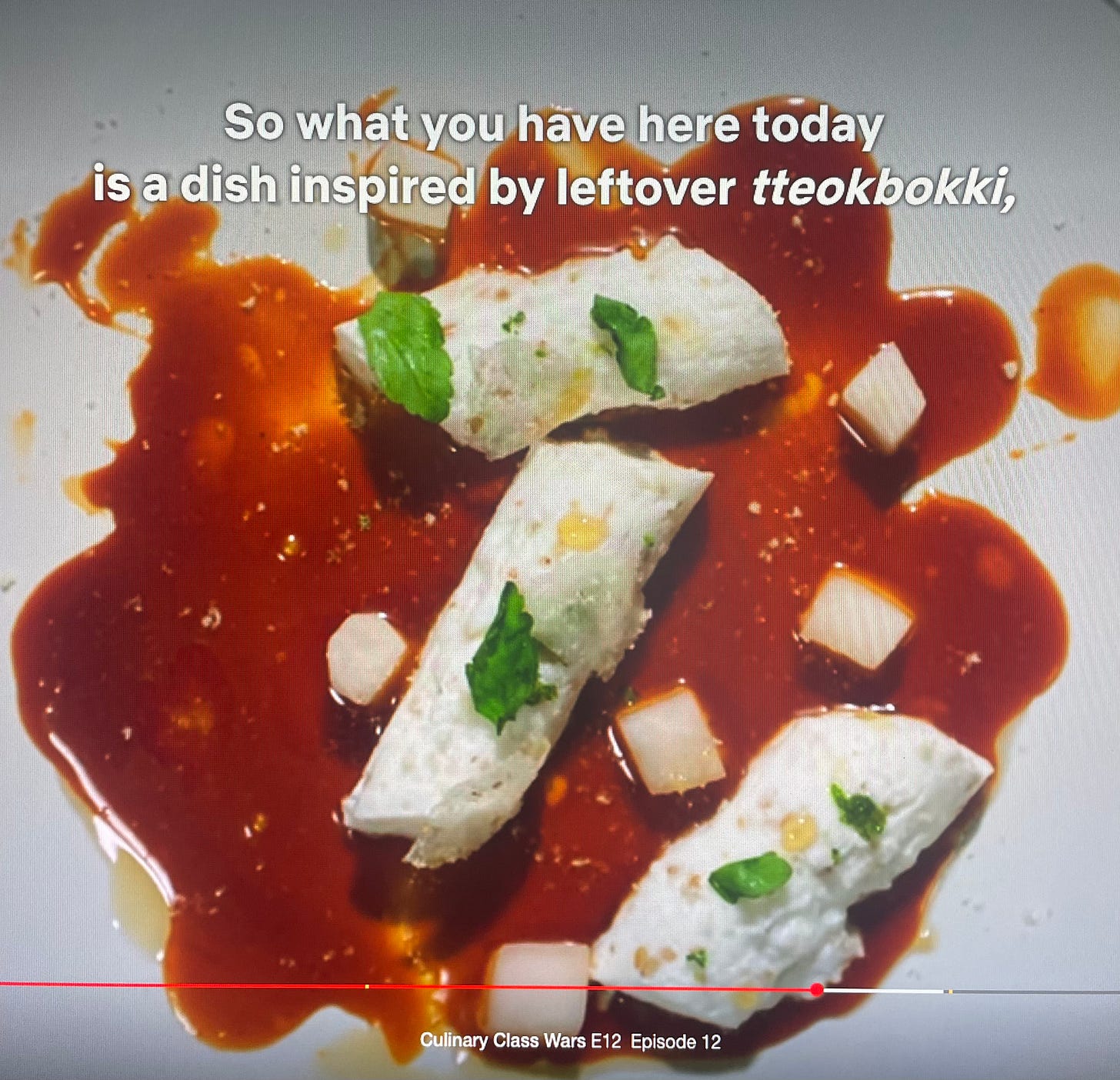

An immediate example that illustrates this “true change” was Edward Lee’s tteokbokki dish from the Netflix show, (Korean) Culinary Class Wars.

In the final showdown, both contestants were asked to create a dish that they could stake their name on. Edward Lee chose to interpret the savory Korean street food tteokbokki as a sweet dessert.

Unlike racist food, Edward Lee’s story of ttoekbokki was complex, vulnerable, and thoughtful. Just look at this aesthetic:

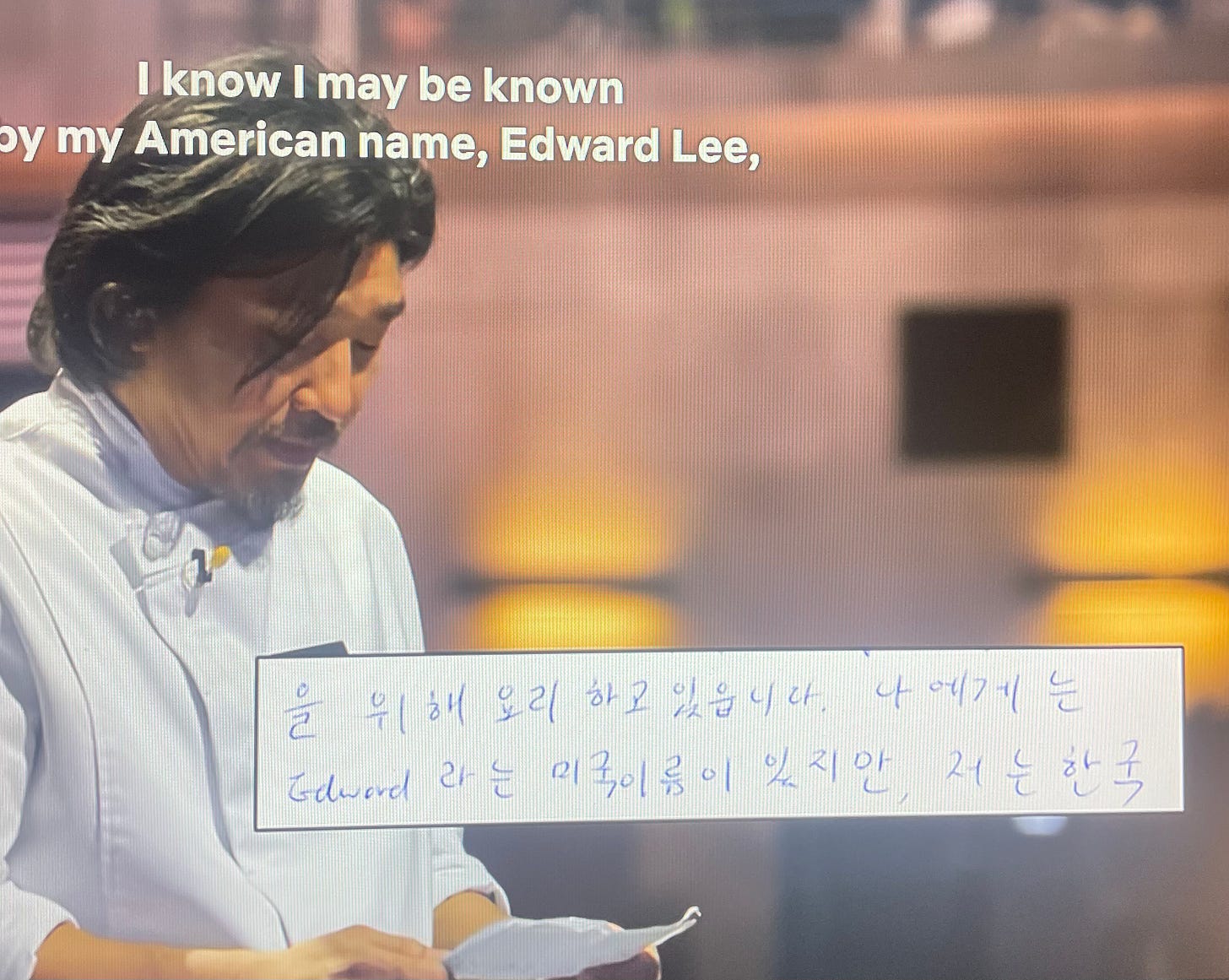

What really moved me to tears was his speech that HE WROTE OUT IN KOREAN (I roughly transcribed this here for y’all because I love you):

“I have an English name, but I also have a Korean name: Kyun. You could say that this dish was made by Kyun.

Whenever I ordered food from Korea, they always gave me so much. I could never finish it, especially tteokbokki. They give me so much that I would always have two or three pieces of rice cakes leftover.

I used to think that this was just wasting food, but not anymore. I know that the spirit of Korean food is about generosity, food prepared with love, and consideration for others.

This is why, today, I’ve prepared this dessert with that symbolize the leftover rice cake pieces.”

You really have to watch this clip because just reading the words here don’t do it justice. It’s not just his words that are so powerful. It’s his trembling tone, the trembling hands, the child-like Korean coming out from an elderly man.

What I loved the most is that Edward Lee truly changed. Lee used to think that the spirit of Korean food was wasteful, and this simple narrative could have easily remain justified in his mind for the rest of his life.

But something happened. I’m not entirely sure what it was exactly, but here’s what I do know. This man gets it.

His humble posture towards Southern cooking, and his willingness to give credit to the founders of the cuisine is quite rare in the restaurant industry where innovation and originality is idealized.

Or the Lee initiative, the non-profit he founded which seeks to make fine dining a more equitable, diverse, and sustainable endeavor. Doesn’t this speak to his ability to imagine a better world not just for those that “make it” but everyone?

I’m guessing that some of this might have bled into his wrestling with his Korean-American identity.

Alright, who tryna go with me to Kentucky to eat at his restaurant? YEEEEEE

Readers, does any of this resonate with you? Is there a food that made you feel small?

Better yet, is there a food that gave you dignity?

I’m Curious to hear people’s thoughts!!!

ALL ABOARD THE TABLE FABLES TRAIN, FIRST STOP KENTUCKY.

Great piece man